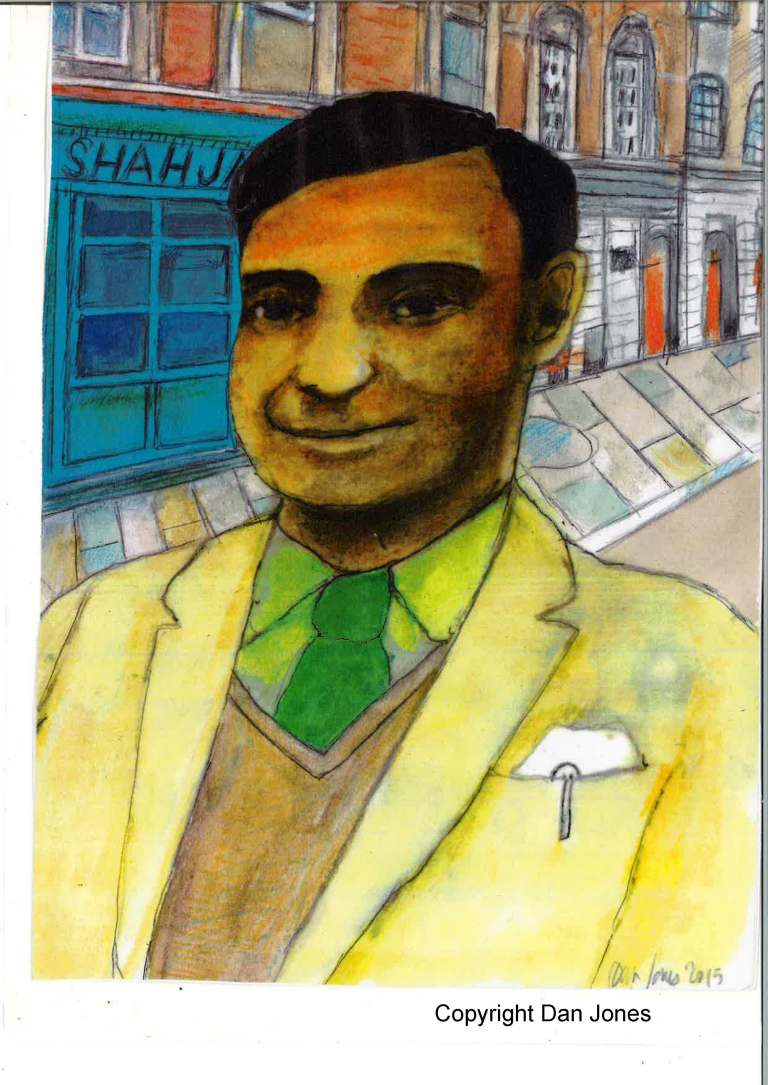

Most people think that Bengalis came to England in the 1970’s or 80’s but I’m going to tell you about Ayub Ali Master who came here much before.

Most people think that Bengalis came to England in the 1970’s or 80’s but I’m going to tell you about Ayub Ali Master who came here much before.

Ayub Ali was supposedly born on 1st January in 1880, (precise date of birth unknown) in Sylhet, Bangladesh, then a part of British India. Many Bengali men took the 1st of January as their birth date because either they didn’t know or didn’t care about such things but it was important to have one when applying for documents e.g. passports etc. He made his way to London around 1st January 1920 (again, precise date unknown) via the United States, having jumped ship there in 1919 but nobody knows why and how he got to America in the first place…

When he came to England he set up the Shah Jalal Restaurant at 76 Commercial Street, in the heart of the East End. The food in England was so revolting that many Bengali men were extremely grateful to go somewhere where they could get something decent to eat that wasn’t bland and boring like brown Windsor soup. The café served as a hub for the early Bengali community there.

Ayub Ali took care of Lascars that had jumped ship and were therefore wanted by the ship companies for being in breach of their contract. He gave them free food and shelter and helped them register at India House and the local police station. When they got jobs, many would go on to rent rooms in his house in Sandy’s Row, known locally as ‘Number Thirteen’, where they would continue to receive support from Ali in the form of letter reading and writing, and help with remittances to India. He was known by them as ‘Master’, because of his education and the way he had with words.

Ayub Ali Master formalized his social welfare work among Lascars when he founded the Indian Seamen’s Welfare League with Shah Abdul Majid Qureshi in 1943: “In order to remove the long felt want of the Indian seamen in London to have a centre of friendly meeting and recreation of their own, a Club has been recently organised under the name of the ‘Indian Seamen’s Welfare League’. The aim and object of this Club is purely to provide social amenities for the Indian seamen and their friends”.

The organization had its office in Christian Street and its stated aim was ‘to look after the economic, social and cultural interests of Indian seamen, to provide them with recreation in Great Britain and to communicate with their relatives in India in the event of any misfortunes befalling them’

Letter from Master Ali on behalf of the Indian Seamen’s Welfare League to Clan Line, St Mary Axe, EC3, 22 June 1943: I am…directed to invite you to a memorial meeting in honour of the Indian seamen who have lost their lives in the course of their duties in this war. The meeting will be held under the auspices of the Indian Seamen’s Welfare League at 4pm on Sunday, 4th July 1943, at Kings Hall, Commercial Road, Aldgate, London, and E.1. Knowing your interest in the welfare of the Indian seamen, the Welfare League will highly appreciate your presence at such a meeting and will remain grateful for your encouragement and support.

Because Ayub Ali Master was politically active he was kept under the beady eyes of the authorities; an Indian Political Intelligence file titled ‘Indian Seamen: Unrest and Welfare’ includes numerous government surveillance and police reports on the activities of Lascars in Britain in the 1930s and 1940s, focusing in particular on their strikes and other forms of activism against their pay and conditions.

Ayub Ali Master was also involved with the East End branch of the India League (serving as treasurer at one point) whose meetings were frequently held in his café, and is recorded as present at the 1943 protest meeting of the Jamaat-ul-Muslimin at their dismissal from the East London Mosque by its trustees.

The Indian Seamen’s Welfare League changed its name from the Indian Seamen’s Union because they did not want the organization to appear too political – in part because they wanted recognition from ship-owners, and in part to avoid attention from the police. A letter from Ayub Ali to the Clan Line is further indication of the organization’s attempts to build bridges between lascars and their bosses. In spite of this, however – and in spite of Ali’s insistence in the letter of the purely social nature of the League – the inevitable politicization of an organization concerned with the welfare of lascars is evident in the very fact of a meeting ‘in honour of the Indian seamen who have lost their lives in the course of their duties in this war’ and who were no doubt labouring under particularly harsh and dangerous conditions in the employ of the ship companies. The organization’s advisory committee, who worked in the background, included well known political activists in the India League and Swaraj House – such as D. B. Vakil, Surat Alley, Tarapada Basu, B. B. Ray Chaudhuri, Mrs Haidri Bhattacharji and Said Amir Shah – also casting doubt on its self-description as non-political. So there was no getting away that the Indian Seamen’s Union meant business when it came to social justice.

Ayub Ali Master was also president of the UK Muslim League, reportedly mixing with Liaquat Ali Khan and Jinnah. (The founding fathers of Pakistan). He saw his beloved Bengal divided by the British before they quit India in 1947.

Later when many more Bengalis started travelling to the U.K., he went on to start up a travel agency business, Orient Travels, at 13 Sandy’s Row, which later moved to 96 Brick Lane. Ayub Ali Master reportedly died on 1st April 1980 in Bangladesh. His final resting place was his home sweet home.

JULIE BEGUM

Acknowledgements:

Adams, Caroline (ed.) Across Seven Seas and Thirteen Rivers (London: THAP, 1987)

Visram, Rozina, Asians in Britain: 400 Years of History (London: Pluto Press, 2002)

India Office Records, Asian and African Studies Reading Room, British Library, St Pancras